"I can calculate the movement of the stars, but not the madness of men"

[Sir Isaac Newton, after losing a fortune (£20,000) in the bubble]

[Sir Isaac Newton, after losing a fortune (£20,000) in the bubble]

The end of the stockworld

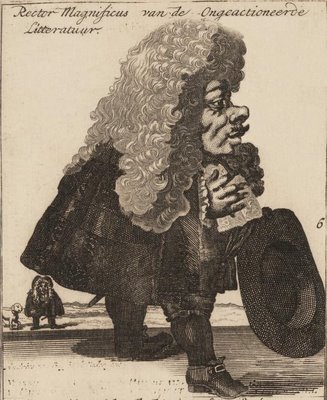

The rector magnificus of un-acti[o]ned (shareless) literature.

Natural stock doctor, or bubbling bubble master.

The night singer of shares, with his magic-lantern.

Contemplation for the greedy world on the rise and fall of the stock-jobbery

The inventor of stock-jobbery in his triumphal car.

The God of schemes has spent his fury and leaves only destruction behind.

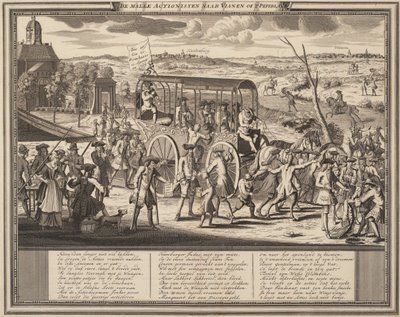

The foolish shareholders on the way to Vianen or the pepperland

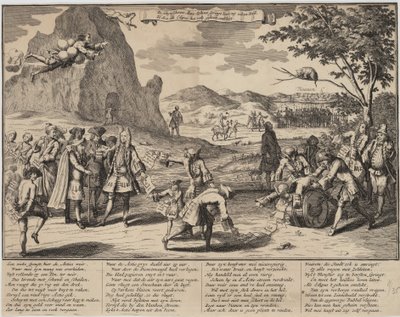

The falsely-fair share-sphinx springs down from the high

rocks, Oedipus having discovered the false secret.

rocks, Oedipus having discovered the false secret.

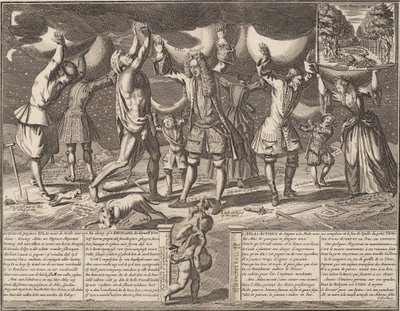

The Atlas of share-paper à la mode with his accomplices.

The active bellows and the spirit of Erasmus, leaving

the city where he was born to visit the three

cities of Holland not affected by share-trading.

the city where he was born to visit the three

cities of Holland not affected by share-trading.

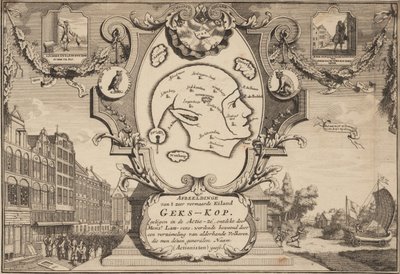

Picture of the very famous island of Madhead, situated

in the Sea of Shares, and inhabited by a collection of all kinds

of people, to whom are given the general name of actionists.

in the Sea of Shares, and inhabited by a collection of all kinds

of people, to whom are given the general name of actionists.

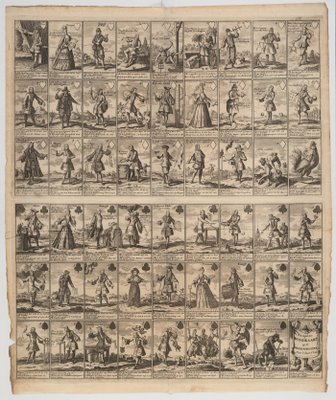

Pasquin's wind card[s] on the wind trade of the year 1720

Many became crazy because they believed in schemes.

Encounter of the carousing bubble lords and menacing poverty.

Ball, or the world in masquerade.

The world's first great stockmarket crash occurred in 1720 in England, France and, to a lesser degree, Holland. Without going much into specifics, if only to prevent my eyes glazing over, there are a few notable names and events associated with these speculative episodes of financial history that help give the illustrative response some context.

John Law acquired the Mississippi Company and established a bank that issued paper money in France and he was given a monopoly to trade with North America. With an effective marketing campaign based on the notion that there were vast quantities of precious metals to be had from the French Louisiana delta, shares were issued and paid for by government debt. Share trading escalated, the price soared on paper, other speculative ventures came out of the woodwork and a large slice of the population lost money when the expected wealth was not forthcoming and both confidence and the stock price eventually plummeted.

In England, a similar scenario developed with the South Sea Company when it was given exclusive trading rights with Spanish South America. The company tried to emulate the same level of public credit manipulation across the English Channel by converting the government debt into company shares and by artificially inflating the share price.

Amsterdam was perhaps the most important trading centre during this period so the fervour for buying and selling shares in dreams and the resulting inflationary pressures was imported.

None of this is rocket science and if hyperinflated share prices, pernicious greed, government and company corruption with attendant price crash and wealth destruction sound familiar, it's because the Mississippi and South Sea bubbles were the forerunners to contemporary collapses like Enron.

The bubbles burst in September 1720 leaving many companies and individuals financially ruined. The artistic response was strongest in Holland although a modest number of satirical cartoons and poems were produced in England and France. The imbalance here probably derives from the uniquely dutch episode in the first half of the 17th century known as tulipomania, where similar overpricing and fevered trading and eventual collapse had resulted in illustration work lampooning wayward business speculation. In other words, there was already something of a tradition, a body of illustration work, from which contemporary artists in Holland could draw upon for inspiration as the stock trading madness unfolded during the year 1720.

The most puzzling aspects are how, why, when and by whom the book containing the above illustrations came into existence. 'Het groote tafereel der dwaasheid : vertoonende de opkomst, voortgang en ondergang der actie, bubbel en windnegotie, in Vrankryk, Engeland, en de Nederlanden, gepleegt in den jaare MDCCXX' has a title page that translates as:

'The Great Mirror of Folly, showing the rise, progress, and downfall of the bubble in stocks and windy specualation, especially in France, England and the Netherlands in the year 1720, being a collection of all the terms and proposals of the incorporated companies for insurance, navigation, trade, &c. in the Netherlands, both those of which have gone into actual operation and those which have been rejected by the legislatures in various provinces. With prints, comedies, and poems, published by various amateurs, scoffing at this terrible and deceitful trade, by which various families and persons of high and low condition were ruined in this year, and possessions lost, and honest trade stopped, not only in France and England but in the Netherlands.

As long as the avaricious

Own money and property,

The deceitful man gains his end,

For the miser and the fool will always feed him.

Printed as a warning to those who come after, in the ill-fated year, for many fools and wise men. 1720.'

Each particular issue of the book is said to be unique, cobbled together on demand so it appears, by an unknown Amsterdam printer and containing anywhere from 49 to 74 illustrations from the work of up to 56 different engravers. It seems astonishing that such a publication could be compiled in the few months following the financial collapse in September and be released in the same year. The inclusion of the date in the title may otherwise have been part of the compiler's desire to give immediacy to the sense of moral indignance they wished to convey, if, as has been supposed by some, that it was in fact first released after 1720. Many editions were published throughout the 18th century. This is one bibliographic record worth reading about (says he who usually shys away from the printing history) - in the extended 1949 essay by Arthur Harrison Cole: 'The Great Mirror of Folly ('Het Groote Tafereel der Dwaasheid') an Economic-Bibliographical Study'.

So the illustrations here are worth looking at in detail as they variously combine contemporary allusions (names, companies etc) with classical themes ( ancient Gods for instance) and mocking satire (trading in 'wind' is a prevalent visual metaphor, as is money being shat out by many of the characters). I had seen a few of these before (the caricatured little people are at NYPL if I remember correctly; and the fools map is also quite common) but never knew any of the background. Incidentally, this evolving mélange of a book also included one of the first maps to name New Orleans.

'The Mirror of Folly' illustrations are part of a larger website at Harvard University - The South Sea Bubble Collection - but I've hardly looked into the rest of the site which includes further satires, playing cards (different to the set above), poems and songs among other things.

{via Tellurianmonkey at Hanuman } [previously]

No comments:

Post a Comment