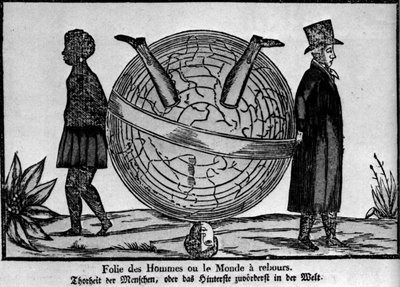

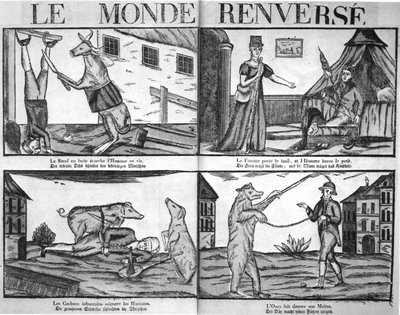

Deckherr [detail] 1820 -

variations on this motif appear in the great majority of prints

variations on this motif appear in the great majority of prints

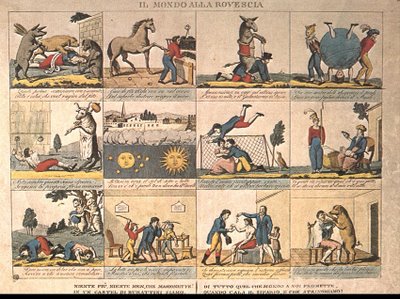

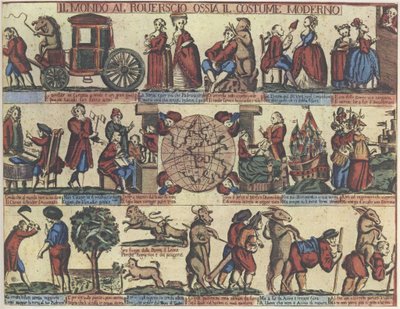

'Cosi Va Il Mondo Alla Riversa' 1560 (anon.)

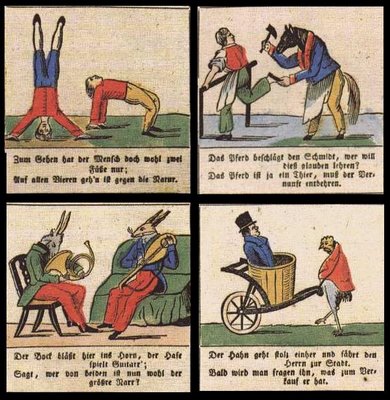

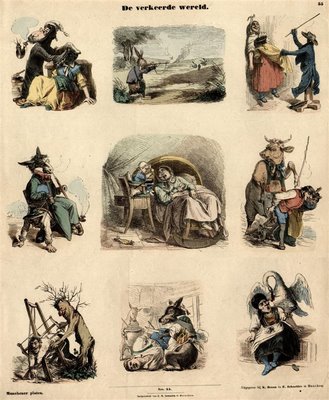

Khun [details] 1830

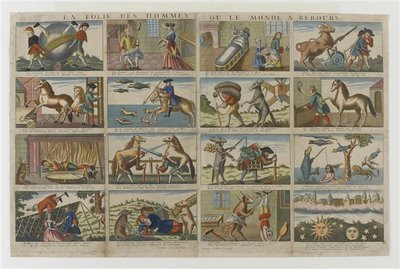

Monhard 1765

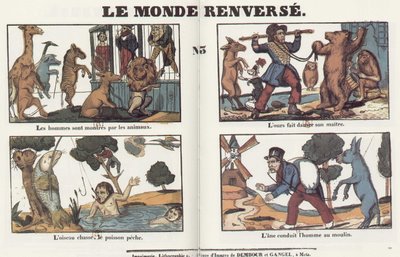

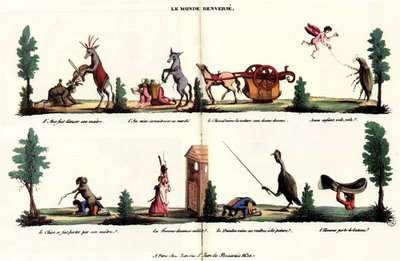

Dembourl 1840

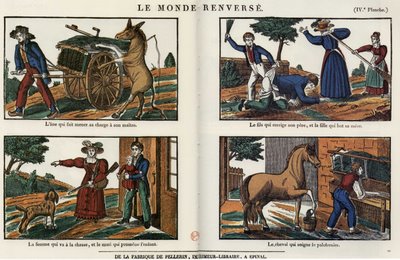

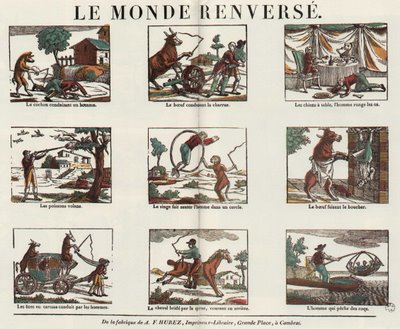

Pellerin 1829

Braun 1872

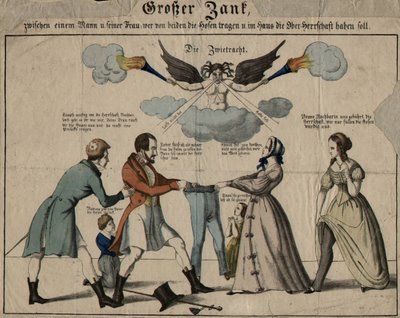

Grosserzank (not strictly part of the genre perhaps) ?date

Toscane 1825

Raab 1826

Deckherr 1820

Desfeuilles 1820

Hurez 1817

Jean 1800

Kunckelbrieff 1630

Remondini 1720

[click on images for greater detail -

either the printer or artist is named with the year]

I recently stumbled across a couple of quirky prints from a few hundred years ago in childrens' book databases that depicted absurdist role reversals. I found them intriguing and posted them here but didn't give them too much consideration - I thought the themes were pretty universal in comedic illustrations and I couldn't deduce how I would be able to specifically identify them to search for more.

The other day I happened upon an extensive dutch database of these simplistic woodcuts and engravings within the 'Stichting Geschiedenis Kinder- en Jeugdliteratuur' (Foundation of Historical Children/Youth Literature).

This genre was known variously as 'Le Monde Renversé' 'De Verkeerde Wereld' 'Mundus Perversus' 'El Mundo al Revés' 'Il Mondo alla Riversa' or 'Topsy-Turvy World' and is first identified in a 1560 anonymous italian print (2nd image from top). [Pieter Bruegel's 'The Fight Between Carnival and Lent' 1559 is said to be an influence or overture to the style]**

I've read (poor) translations of much of the commentary at the website and they outline a few standard characteristics of the genre design:

- Inversion of the normal social order (eg. child punishing the parent)

- Relationships between people and animals (eg. donkey being carried by man)

- Relationships between animals (eg. rabbit hunting the fox)

- Relationships between objects (eg. ships sailing in a mountain range)

It's thought that the Reformation and diminshing power of the church as well as various insurrections and wars across Europe and the great voyages and discoveries of new lands (and in science) during the 16th century was a fertile backdrop in which satrical images of the world being overturned could become popular.

There is something of an intentional ambiguity in a lot of the images (or complete obscurity in some) - the artist was being a social critic, possibly advocating a change in social order on the one hand or ensuring that social norms were obeyed - depending on how you regarded them. Of course, the primary motive was humour and divining profound allegorical or metaphorical intent was not necessary to enjoy them at face value.

[For instance, a few of the images above show the man looking after an infant and the woman armed with a gun -- on one view, that might be regarded as a subtle message on the subject of emancipation - in any event, the website has provided a lengthy bibliography of works both about the genre and their social relevance]

Unfortunately, the cheap nature of the printing means that there are few examples online of high quality. I tried to select the better prints but there are many more of varying resolution and quality to see at the website. The 4th image above comes from the Joconde database -- there are a few bits and pieces in many languages online (nothing in english) but the hetoudekinderboek site [frameless] appears to have assembled the vast majority anyway.

**Sharon at Early Modern Notes gives a short review of the role of carnivals in medieval times, which has a direct influence upon/relationship with 'Le Monde Renversé'.

No comments:

Post a Comment